Written by Jeremy Lloyd, Manager of Field and College Programs. This piece originally appeared online in the Knoxville News Sentinel on Sunday, September 13, 2020, and in print on Sunday, September 20, 2020.

Among the most joy-filled moments I’ve experienced since the start of the pandemic have been those I shared recently with children in the Lonsdale neighborhood. Every minute of our time together was spent outdoors in nature. These were moments that were both revealing and confirmed everything I know about the critical importance of utilizing the outdoors as a classroom space for students.

Allow me to explain.

For the past twenty years, I’ve taught experiential education focused on the natural world at Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont. We have remained shuttered since March, unable to host thousands of students, educators, and adult learners who attend our residential programs inside the national park.

While grappling with this new reality, we have been forced to let half our staff go and explore fresh and innovative ways to fulfill our mission of connecting people and nature. One natural fit was working with local Boys and Girls Clubs on a temporary basis. Rather than students coming to us as they have since our founding in 1969, we would go to them.

This was new territory for me. Taking children on a wilderness hike where we might encounter black bears and rattlesnakes? No problem. Conducting classes in meadows, forests, and creeks in any kind of weather? Sign me up.

But teaching kids in an unfamiliar urban setting, and departing the school grounds altogether on a trek through the neighborhood? This was a stretch. Perhaps, though, it was just the kind of uncertainty that all the other uncertainties caused by the coronavirus crisis had prepared me to face.

It rained the first day, though it hardly mattered. Handing out bug-boxes in the Lonsdale Elementary schoolyard, I watched as the students turned over logs and dig in the dirt in search of pillbugs and centipedes. The next hour we ventured into a nearby greenspace where they caught minnows in a litter-strewn creek. On the next visit, we lit out on a bigger adventure to Racheff Park and Garden.

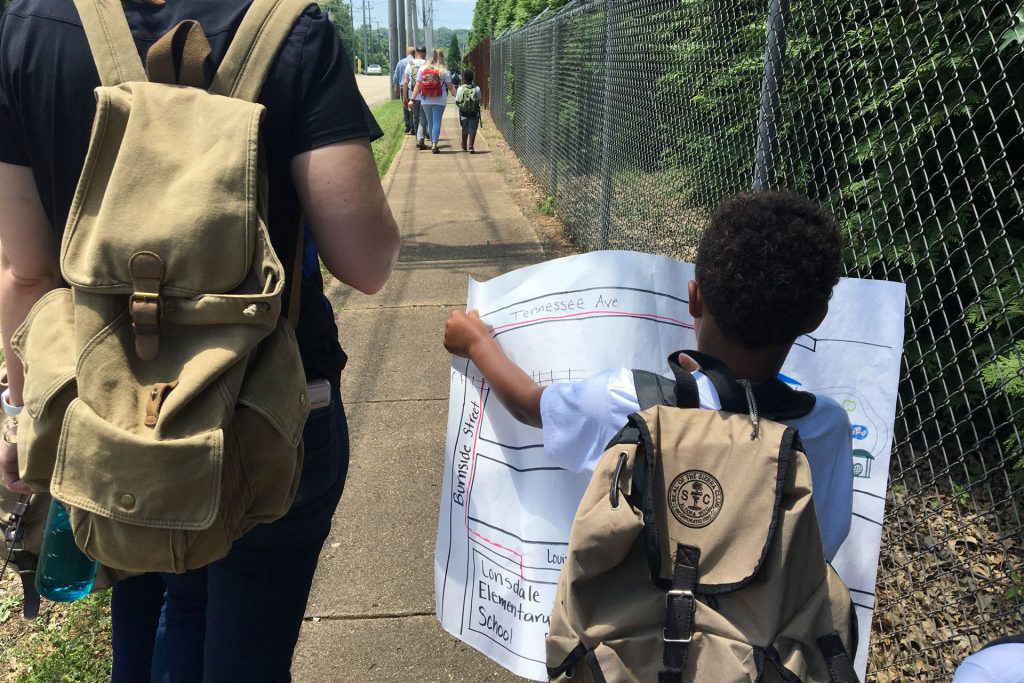

Here’s what I learned on our one-mile city walk: that moving trains and tractor-trailers and a busy industrial site are not impediments to learning but instead comprise a fascinating landscape even eight and nine-year-olds can be trusted to safely navigate and learn within.

That students thrive when given an opportunity to study their world firsthand, and become more caring toward one another and more invested in their own learning.

That for educators a chance sighting of passionflower, Tennessee’s state wildflower, growing in an industrial waste site, becomes a teachable moment of equal importance to planned activities and curriculum.

That being outdoors anywhere at all makes people happier, healthier, and more at home in the world, as troubled as it is right now.

But I came away with several pressing questions too: Why can’t such moments become a regular occurrence for students in Knox County and throughout East Tennessee during the school year? Why can’t they become a normal part of the school day?

For many schools, safety concerns don’t appear to be the primary obstacle. After all, nearly one hundred schools from more than a dozen states attend Tremont programs annually, demonstrating many administrators’ approval for immersing students in an environment of the bears-and-snakes variety.

Nor is resistance from teachers, who already have so much on their plates, the reason. Of the hundreds who attend our educator workshops each year, an overwhelming majority express enthusiasm for wanting to take their students outdoors back at school.

So what is the holdup? The answer is: our way of thinking.

It’s the assumptions we make about what constitutes a classroom. Many of those assumptions are based on an outdated factory model adopted by Massachusetts educator Horace Mann after encountering it in Europe in the 19th century. For more than a century, it has bolstered the dominant image for student reality: rows upon rows of students sitting at desks all day long.

These days, as we Americans reconsider our priorities and commitments, I would urge school administrators to think outside the box and to rethink the boundaries of their school’s classroom spaces by expanding them outdoors. Now would be an ideal time to empower and equip teachers to find balance between screen time and schoolyard time while still meeting school standards.

Taking students outdoors by no means eases every concern educators have about resuming school this fall. Yet we know the alternatives—online classes and crowded classrooms—have significant drawbacks. Research has shown that the chances of contracting the virus outdoors are far fewer.

Moving the classroom outdoors, I hasten to add, shouldn’t mean conducting business as usual only beneath the cover of a tent. It should mean harnessing local assets and opportunities, just like we did as a group at Lonsdale.

A tree becomes a math problem (circumference, radius, and height). A shovel-full of playground dirt becomes a study in geology and biology. An inventory of the soundscape in an urban neighborhood becomes a lesson in civics, economics, and sociology. And too, these shared experiences of learning outdoors together provide something more than just academic lessons by incorporating learning that is also social and emotional.

Viewing the world—the classroom—in this way requires a shift in thinking, in attitudes, and in perceptions. It doesn’t mean making a leap so much as taking that first step. Once that step is taken, a whole new world of opportunities opens up, ready to be adopted more fully in our schools. The benefits are boundless: more curiosity and optimism, increased resilience, and excitement for learning.

What are we waiting for?

You can help by joining Tremont’s new Schoolyard Network. Let’s work together to bring our students outdoors.

![A Deep Dive Into Wetlands [Free Lesson Plan]](https://gsmit.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/madeline-blog-cover-500x383.png)