Written by Robert Schmidt, Teacher Naturalist at Tremont

Helpful Terms

- Nymph: The aquatic stage in many insects’ life cycle including stoneflies and mayflies.

- Nymphing: fishing with flies that mimic these insects, done under the surface of the water.

- Eddy line: A place where moving water is sliding past not moving water. Looks like a line of small whirlpools.

- Salmonid: A member of the Salmonidae family, includes trout, salmon, char, whitefish, and graylings.

Up to my waist in the cold clear water of the Middle Prong, I flop my nymph to the top of an eddy line as the current comes around a rock. I watch my line straighten out, letting my nymph settle towards, but not on, the bottom of the river. The key is having a straight line between the rod tip and the nymph. This technique helps you detect the strike. My rod tip mimics the motion of the current and, in turn, under the water mimics a mayfly nymph that got swept up in the current. At least that’s the idea.

Like the fish, I come from someplace else and now call the Middle Prong home. I was lucky enough to choose my new home. For the rainbow trout, it is a different story.

Feeling and looking for anything that seems fishy, I see the bow of my line straighten out ever so slightly. Without knowing if I hit a rock, I bring my rod tip up, driving the point of my hook home. I feel the explosive motion of a hooked fish as my rod bends. The connection is made.

Immediately the fish bolts out from the eddy into the current. Feeling the additional resistance of the flow, I pay out some line. Balance must be maintained. I don’t want the fish to break off the thin monofilament so I let out line. But if I let out too much, the fish could easily shake out my barbless hook. It’s a tricky business. The fish makes a move back into the eddy downstream from me, the calm water letting me unite my net and the fish. Once in the net, the fish gives one shake of its head and dislodges my nymph. Good ole barbless hooks.

The tired fish now in my net is a rainbow trout. Indeed in the Middle Prong anglers mostly catch rainbows. I wet my hands and pick up the fish for a closer look. Measured against my arm, I would say it is about 11 inches. Only thirty percent of rainbow trout in the park grow past eight inches. It is not very big as the species grows, but here it is slightly above average. This contrast in sizing only makes sense because this is not their native home.

As I let the fish swim on, I reflect on where we find ourselves. Like the fish, I come from someplace else and now call the Middle Prong home. I was lucky enough to choose my new home. For the rainbow trout, it is a different story.

Anglers come from across the country to fish in the Park. Today folks can get a shot at brook, rainbow, and brown trout in the 2,000 plus miles of streams in our national park. That was not always the case.

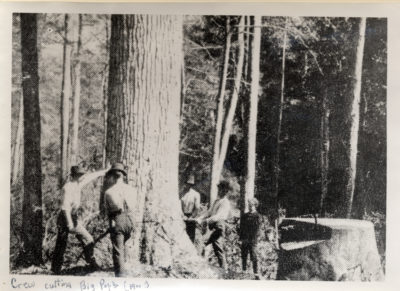

Before 1934 the only salmonid here was the brook trout, caught mostly for food. The brook trout — not a true trout but a kind of char — was once present in all streams above 2,000 feet but got pushed out of 75 percent of its historic range. By the 1880s, logging companies laid steel rails up the river and the advent of locomotives that could handle the rugged terrain of the mountains triggered a logging boom. Massive areas of forest were cut down. By the end of the boom, 60 percent of all trees in the park were cut into lumber. Without roots to hold the soil, massive amounts of sediment washed into the waterway. This added to the ash from rampant fires in the wake of clear-cutting to leave the rivers choked and running brown. With no shade from trees, the river temperature went up, and brook trout populations went down.

Before 1934 the only salmonid here was the brook trout, caught mostly for food. The brook trout — not a true trout but a kind of char — was once present in all streams above 2,000 feet but got pushed out of 75 percent of its historic range. By the 1880s, logging companies laid steel rails up the river and the advent of locomotives that could handle the rugged terrain of the mountains triggered a logging boom. Massive areas of forest were cut down. By the end of the boom, 60 percent of all trees in the park were cut into lumber. Without roots to hold the soil, massive amounts of sediment washed into the waterway. This added to the ash from rampant fires in the wake of clear-cutting to leave the rivers choked and running brown. With no shade from trees, the river temperature went up, and brook trout populations went down.

As the last logs came out of the park in 1938, the transient workers who lived and labored within the sound of the river followed in their wake. Tracing the steel rails they laid by the river, the loggers picked up tracks and entire towns built up around cutting trees. Today it is still possible to see forgotten artifacts left behind — things that tired workers did not notice or did not care enough to remove fell to the wayside. The logging industry left the rivers a shell of what was once a hospitable watershed. The otter, beaver, and brook trout could no longer be found.

In 1934, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established, protecting the land from future industry, and the National Park Service started a program to introduce rainbow and brown trout to promote a fledgling sport fishing industry. Rainbow trout are one of the native species of trout found in the western United States. After being pushed out of waterways, the native brook trout could not compete with the rainbows in the newly recovering rivers and streams. Brown trout, reaching the largest sizes of up to 30 inches and known for their piscivorous (fish-eating) habits, have only been stocked once but continue to breed and work their way upstream from some lower elevation rivers. The park also stocked northern strains of brook trout to keep the population alive. After the park re-evaluated the practice, fish stocking of non-native species came to a halt in 1975.

In 1934, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established, protecting the land from future industry, and the National Park Service started a program to introduce rainbow and brown trout to promote a fledgling sport fishing industry. Rainbow trout are one of the native species of trout found in the western United States. After being pushed out of waterways, the native brook trout could not compete with the rainbows in the newly recovering rivers and streams. Brown trout, reaching the largest sizes of up to 30 inches and known for their piscivorous (fish-eating) habits, have only been stocked once but continue to breed and work their way upstream from some lower elevation rivers. The park also stocked northern strains of brook trout to keep the population alive. After the park re-evaluated the practice, fish stocking of non-native species came to a halt in 1975.

As the trees grew back, the land healed. Then the water healed. Otters were successfully reintroduced, and beavers came back to be the only creatures to cut trees along the waterways of the Smokies. In the high-altitude streams, protected by waterfalls impassible by rainbow and brown, brook trout live on.

Our watershed has rebounded from ecological devastation to the thriving habitat we have today. Much progress has been made but this process is ongoing. Native or not, there are healthy, wild breeding populations of brown and rainbow trout in our 2,000+ miles of stream today. Brook trout can still be stalked and caught in streams protected by waterfalls or dams. Today along the banks of the rivers in the park, you can find rods bent as people from around the world connect with the fish and in turn, the ecosystem that surrounds them.

If you plan to fish in the park, make sure you are familiar with the regulations in place. You can find most of the information on the national park’s website online: https://www.nps.gov/grsm/planyourvisit/fishing.htm

All of our help is needed to ensure the health of our rivers in the Smokies. May their waters be healthy for future generations for years to come.

Here are some of the places I found information for this post:

- National Park Service

- Trout Fishing in the Smokies and the Blue Ridge, 1880-Present: How-To, History, and Habitat by Nathaniel Cole Skaggs