Hello Avian Enthusiasts!

We are in the transitional period of autumn when leaves are falling, temperatures are changing, and many of our summer resident birds have long since left the valley to travel south to their overwintering grounds. As we notice migrating warblers passing through and winter residents settling in, let’s take a look back at our summer bird banding season to see what our feathered family tried to teach us about their health and populations.

With the support of a phenomenal team of community science volunteers, we banded a total of 62 birds this summer, and 17 different species were caught and safely released from mist nets, a tool for ornithology (the study of birds). Here are a few of our notable visitors on Tremont’s campus:

Brown Thrasher. Photo by Clare Dittilo.

- A Brown Thrasher ran into the bottom of one of our field nets. Brown thrashers do much of their foraging on the ground, using their beaks to sort through the leaf litter to find food. We don’t normally catch ground birds! This startled male bird was likely not too happy to have run right into the bottom rung of our nets, but he was released unharmed after some admiration from the local humans.

- Acadian Flycatchers were busy this year, and we banded 5 individuals, mostly caught in our nets by the parking area across the bridge on Tremont Road.

- Our beloved warbler species, the Louisiana Waterthrush, was well represented this year, with a whopping 24 individuals caught and banded this summer!

Why Do We Band Birds?

At Tremont, we run a banding station that contributes data to a program called Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship, or MAPS (more info here). There are stations following the same bird banding protocols as ours all over North America, including Canada and Northern Mexico. You can check the map of MAPS stations here. With so many banding stations, you can imagine scientists are able to get a TON of data about birds and their breeding habits, including the age, preferred habitat use (are we catching them in field nets or nets next to rivers?), and avian diversity at different sites.

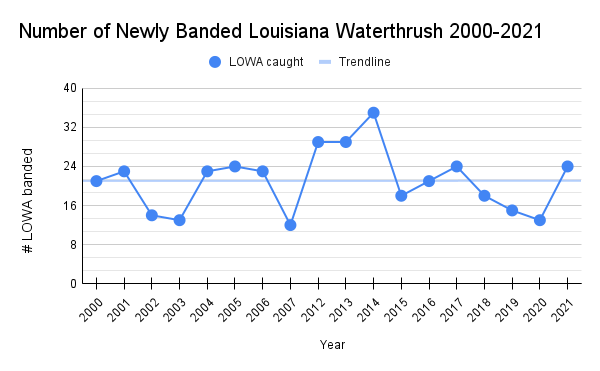

Internally, we can use our data to check up on our feathered neighbors, and monitor their population health by comparing how many individuals of a given species we catch each year (Figure 1, for example). If we notice a sudden drop in population that lasts a few years, that could indicate a negative trend in population, and we would have a launching point to investigate what might be contributing to their decline.

Figure 1. Louisiana Waterthrush (LOWA) new captures at the Tremont MAPS station from 2000 to 2021. Data from 2008-2011 not available. What do you notice about the trendline?

From the above graph of Louisiana Waterthrush (LOWA), we can see that there is no significant trend up or down, meaning there were no significant changes in the number of LOWAs being caught in our nets, and, by proxy, living in the valley over this period. While there may be much variation year to year, the overall trend is that of a stable population.

How Can You Get Involved?

We love contributing to national research through our community science programs (learn about our other projects here), and benefit from understanding the health of our summer resident populations. Even more importantly, we love sharing the joy and awe of birdwatching with people who can then go out and notice birds in their own backyards or local parks. While banding can be engaging and useful, there are many ways to contribute to science for birds without banding. At home, eBird and Project Feederwatch are both excellent ways to contribute to science in your own community!

Happy Birding,

Erin Canter

Manager of Science Literacy and Research

Acknowledgements

In lieu of public bird banding days, we got a chance to host some awesome Tremont campers and local partners in 2021, including folks from our Girls in Science and Family camps, The Boys and Girls Club from Vestal in Knoxville, interns from Discover Life in America (DLIA) and the National Park Service, and of course our extremely dedicated Tremont volunteers (listed below).

Huge thanks for the incredible team that keeps birds safe and helps to educate: Dattilo Family, Metcalf Family, Holly Hoyle, Stephanie Mueller, Grace Bobo, Gar Secrist, Warren Bielenberg, the DLIA team (Will, Florencia, Xavier, Madeline), the NPS team (Paul, Callia, Kahawis, Troi, Ana), and of course, our Summer Community Science Educator: Steph “Steve” Busse.

Cover image by Warren Bielenberg.