Written by Grayson Shelor, Teacher Naturalist at Tremont

“Don’t step on the science!”

The handful of family camp participants playing camouflage on Tremont’s nature trail instantly jump back from the roped-off area. But one youngster has questions: “Hasn’t that experiment been there for years?”

Children respect science as a pro-social mission of discovery which takes precedence over games, but I’ve found that they typically expect instantaneous results. The chemistry set is meant to release puffs of brightly colored smoke. The scientist must wipe their foggy glasses on their white lab coat and mutter, “Eureka!”

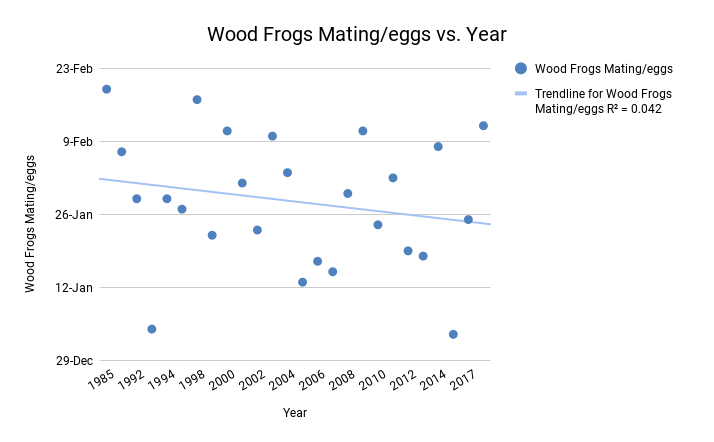

But the science in question on the nature trail is a phenology plot, meant to allow community science volunteers to document the timing of seasonal events across decades. Taking years is the whole point.

Phenology helps us to understand the ways that species’ wellbeing are fundamentally intertwined.

Pipevine Swallowtails are distinguishable from the similarly colored Spicebush Swallowtail by the single arch of orange spots on the outer wing.

For example, Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies are reliant on pipevine as a larval host plant. Tremont data reveals that our earliest recorded sighting of an adult swallowtail is already before the pipevine (sometimes called Dutchman’s Pipe) blooms. Plotting trends in timing leads us to a concerning series of hypotheticals: What happens if the butterflies return* before the pipevine has leafed out? If such a seasonal mismatch were to decrease pipevine swallowtail populations, what might be the effect for spicebush & black swallowtails, or red-spotted purples–who rely on their resemblance to the yucky-tasting pipevine swallowtail for protection from their own predators? And to the birds whose diet they supplement?

*Unlike Monarch butterflies, who migrate over vast distances to winter in the warmer climate of Mexico, Pipevine Swallowtails overwinter as chrysalides, meaning that they complete their extended metamorphosis that began the previous fall and hatch as butterflies in the early spring. Therefore, ‘emerge’ might be a more apt term than ‘return’.

A thriving, biodiverse ecosystem relies upon intricately choreographed sequences of seasonal events. Making sense of such interdependence requires both projecting forward through climate and management shifts, and reflecting on data from the past. Consistent observation is crucial to providing a deep pool of data that allows us to separate persuasive trends from the noise of natural variance.

One of the many features of phenology that make it particularly appropriate for community science is that it requires little specialized training–just an enhanced ability to notice details about the natural world. This kind of seeing can necessitate a mindset shift, as I discovered in early July while taking part in Tremont’s annual campus butterfly count.

At first, I scanned the skies for the large and colorful butterflies I expected to see: Monarchs and Tiger Swallowtails. I thought the butterflies would never come. Yet as I began to focus in and turn my gaze to the high grass margins, I discovered an abundance of life I’d never noticed. Within our small team of surveyors, we began to call out detailed observations to collaboratively identify butterflies on the wing. ‘Did you get a good look at the inner wing? Did the markings change near the wingtips? What about the antennae?

As we gathered around a small, orange-brown, and quick-flitting specimen, I read from our guidebook about the chief distinctions between two common look-alike species, the Pearl Crescent and the Silvery Checkerspot. Pearl Crescents are generalist species, able to thrive in disturbed or imperfectly-matched environments. In addition to open fields, you’ll often find them (along with many other species) sampling the nutrient buffet that is fresh mammal scat. In contrast, the Silvery Checkerspot is more particular in its chosen plants, with a special preference for Rudbeckia, sunflowers, and wingstem. Throughout our day of surveying at Tremonts’ two campuses, we encountered 66 Pearl Crescents. And when we finally did encounter Silvery Checkerspots, I was intrigued to note that they clustered around the plots of pollinator-friendly wildflowers intentionally planted by another researcher.

Fast forward to early October’s Monarch tagging events, and a similar pattern holds true: while vibrantly orange Monarchs on magenta thistle are eye-catching, they proved far more elusive than the common Buckeye butterfly. Armed with a net and accompanied by 20 young community scientists from Girls Inc of Oak Ridge, TN, I set out determined to swish up a high-flying Monarch. I ended up entranced with the lifelike eyespots on the Buckeye’s wingtips, an eerie deterrent to predators who might snack on the mid-sized butterflies while they feast on native grassland weeds.

At the risk of anthropomorphizing, it can be easy to imbue generalist species with the admirable human qualities of perseverance and resilience. We naturally admire the capacity to ‘bloom where one is planted.’ Yet from an ecological perspective, we paint a comprehensive picture by documenting the full range of biodiverse species that inhabit an ecosystem, from the rare to the everyday neighbor. Our world’s most fragile species uniquely assist us to gauge the health of our environment. Niche-adapted and vulnerable organisms like lichens, salamanders, and butterflies dependent upon threatened host or food plants can serve as early warning signs of stress or imbalance. These SOS signals only reach us if we’re closely watching nature’s patterns. But like the introduced native pollinator plants in the meadow, they also offer us the opportunity for a course correction. With patient observation and a scientific outlook, we can cultivate an ecosystem that allows our more specialized species to thrive.

Measured aggregations of data like the slow growth of rings in a mature tree enable us to spot shifting patterns of seasonal events. Yet when it comes to management decisions–what we do with the data we’ve painstakingly gathered– we can instead emulate the smallest of our butterfly species: more apt to flutter in a new direction than to glide on in the same familiar course. Time is of the essence.

Learn more about Tremont’s phenology and butterfly monitoring. Interested in getting involved? Contact Erin via [email protected] to learn more about adopting a plot or volunteering for Monarch tagging in 2023!

Cover image by Rich Bryant.