If Fodderstack Could Speak: Walker Valley Lore

Written by Jeremy Lloyd, Manager of Field Programs and Collegiate Studies and author of A Home in Walker Valley: The Story of Tremont

This occasional series is named for the mountain overlooking the Walker Valley campus of Tremont Institute in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. If Fodderstack Mountain could speak, these are a few things it might reveal.

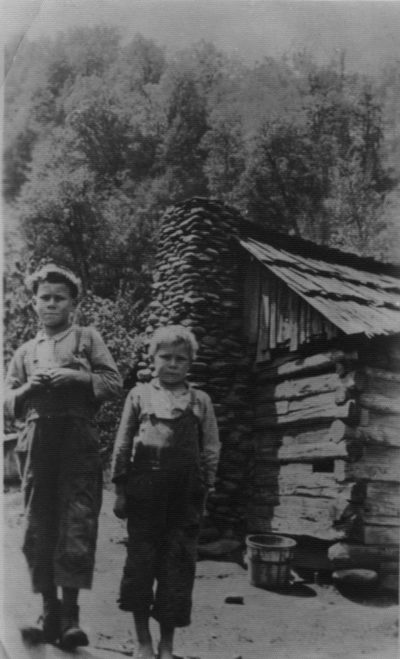

Melvin Ownby, who lived in Walker Valley during the logging era, had a sense of humor.

“There seemed to be a lot of jokes about the mountains—how steep some of them were. One man’s farm was so steep, in order to sow grass seed he loaded his seed in his shotgun and shot the seed on his field from the opposite hillside. The mountains were so steep around one man’s house that he cut his wood above the house and fired his fire from the top of the chimney,” he wrote.

But Ownby didn’t have much to laugh about on the day he got lost in the woods.

“Have you ever been lost? It’s a scary experience,” he wrote. Melvin, along with three other boys, went hunting up Mark’s Creek at the base of Meigs Mountain and got lost. It was dark and raining, but finally they came to an old barn where they spent the night under its eaves.

“When daylight [came] I never say such a strange country,” he wrote. Melvin led the way down Spruce Flats Branch. “We had left home Friday after school and were getting back about three o’clock Saturday afternoon. I can’t recall ever being so wore out or so hungry. But in all our hunts this was the only one we got lost on. We did an awful lot of hunting. We never caught much of anything.”

Parenting trends have of course changed drastically since Ownby’s time. Back then, children were often permitted to roam the woods by themselves, firearm in hand. Today, parents fearful for their children’s safety and well-being keep them indoors more than ever. But are all the real dangers outdoors, or do some of them present themselves through too much time spent staring at screen technologies while cut off from the living, breathing world?

A tragic result of this trend is what lepidopterist Robert Michael Pyle has called the “extinction of experience” for many youth. Is it reversible? That’s up to each parent, each school district, and American culture at large—and the value we all place on providing children with enriching, firsthand experiences in nature.

Melvin Ownby’s account reminds us of what’s possible. Let’s just all be sure to leave out the getting lost part on our next adventure.