Written by Elizabeth Davis, Field Programs Specialist at Tremont. As part of her role on staff, she has lived on Tremont’s campus for about eight years (plus four summers living in the platform tents).

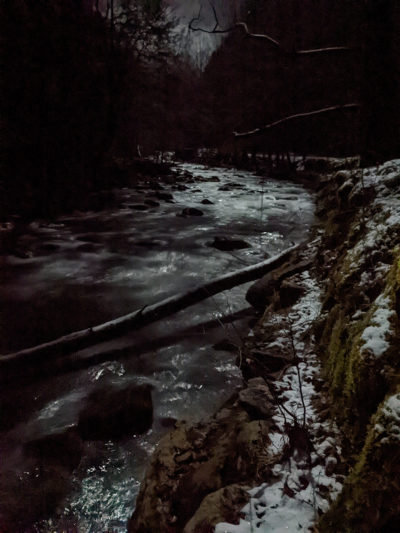

Most evenings, I walk out the back door down to the Middle Prong and wash my face in the water. Some nights, the river breathes out waves of fine fog, discernible only when I switch on the beam of my headlamp. Others, the air is sharp, the sky studded with stars.

Most evenings, I walk out the back door down to the Middle Prong and wash my face in the water. Some nights, the river breathes out waves of fine fog, discernible only when I switch on the beam of my headlamp. Others, the air is sharp, the sky studded with stars.

Author Rebecca Solnit writes, “Sense of place is the sixth sense, an internal compass and map made by memory and spatial perception together.” Memories aren’t old-time movies: silent moving pictures we watch from afar. When we remember, we walk into a rich sensory world of images, but also sounds, smells, and emotions. If you think back to special places in your life- your childhood home, perhaps- it’s all bound up together: laughter, playing tag, and the smell of dirt inseparable from grass-stained knees of jeans and the sound of a distant train.

Each season brings, in turn, its own tapestry of textures, smells, and sounds. In summer, the water flowing through the backyard provides relief from clingy humid stickiness, a refreshing cool crispness before bed. In winter, the daily icy splash jars me awake with animal awareness of the cold, bright, night air. And so, my understanding of Walker Valley is bound to the rhythms of the seasons.

For much of the year at Tremont, our jobs face outward; the work of connecting people with nature is inherently a social occupation. In those busy months, the enthusiasm and curiosity of participants keeps me energized. In a week working with a hundred fifth graders, the daily evening face-splash in the river may be the only moment of stillness, an anchor to the quiet of winter.

When snow falls on Walker Valley, it’s time to pull inward. Roads close. No one drives in or out. Sometimes the river freezes.

When I lived at the Ranger Station down the road, lovingly dubbed “the Oasis” by Tremont staff, a two-week road closure forced us to walk up the slick road a mile and a half to work each day. As we walked, we watched as a small chunk of ice in the river grew, revolving slowly in an eddy, building day by day, until finally, the ice stretched across the river.

Work takes on a slower pace. One day in early January, the three of us still in the valley walked the snowy road past the field down to the office. We were scheduled to work, so we worked. The internet was down due to weather, so we planned for summer programs accompanied by the only music that was downloaded on the old computer in the office: the Hobbit theme song on a continuous loop. We checked the buildings for leaks, set the faucets to drip to prevent the pipes from freezing, and kept an eye out for fallen trees. After work, we explored in the snow, reveling in our aloneness and freedom.

Depending on how you look at it, sledding hills are either abundant or non-existent in this steep-walled river valley. In a worldview framed through the lens of abundance, mountain-side sledding presents a wonderful, though potentially hazardous, opportunity, especially when coupled with an old, beat-up, red kayak left behind by friends and coworkers from an earlier era. The body of a kayak is slick; it’s designed to slip through water with minimal resistance. When applied to a snow-ice-and-tree-covered mountain hillside, a kayak moves quickly and steers unpredictably (think: Calvin and Hobbes). Bruises are a common consequence. So is laughter.

Long hours of darkness bring a special magic to winter. Moonlit walks on Upper Tremont Road, snow and frost sparkling as if millions of stars had fallen from the sky and lodged on the mosses and liverworts among the rocky outcrops. Braided shadows of trees stretched across the road. The absence of frogs, owls, whippoorwills: a conspicuous quiet. Walking barefoot out the back door into the snow, footprints burning cold. Realizing that we are the only people around for miles.

Long hours of darkness bring a special magic to winter. Moonlit walks on Upper Tremont Road, snow and frost sparkling as if millions of stars had fallen from the sky and lodged on the mosses and liverworts among the rocky outcrops. Braided shadows of trees stretched across the road. The absence of frogs, owls, whippoorwills: a conspicuous quiet. Walking barefoot out the back door into the snow, footprints burning cold. Realizing that we are the only people around for miles.

Author and poet Wendell Berry reminds us, “And the world cannot be discovered by a journey of miles, no matter how long, but only by a spiritual journey, a journey of one inch, very arduous and humbling and joyful, by which we arrive at the ground at our feet, and learn to be at home.”

Winter is when we learn to be at home.