If Fodderstack Could Speak: Walker Valley Lore

Written by Jeremy Lloyd, Manager of Field Programs and Collegiate Studies and author of A Home in Walker Valley: The Story of Tremont

This occasional series is named for the mountain overlooking the Walker Valley campus of Tremont Institute in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. If Fodderstack Mountain could speak, these are a few things it might reveal.

A forest is constantly undergoing change, even when people don’t interfere with its natural processes. When humans do intervene, changes are often sudden, far-reaching, and permanent.

The logging era in the first few decades of the 20th century forever altered the forests in the heart of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. With the coming of the national park, however, natural processes were allowed to once more take their own course.

One way humans helped nature “rewild” was by removing manmade structures. Today only ghosts remain of those that once stood in Walker Valley.

One such structure was a tub mill built by Will Walker (possibly one of three) near where the former director’s house currently stands. Though both the mill and the corn that was once milled there are gone, a hollowed-out section of the riverbank indicates the path of the sluice that diverted river water to the tub wheel. It can be seen from Upper Tremont Road, looking across the river just upstream from the old director’s house.

Disruptive natural events were probably as memorable back then as they are today. One was likely the big flood that was said to have occurred in 1928, just a few years after clear-cutting of the forest began. One can only imagine how badly eroded the mountain slopes were by this time, only for heavy rains to compound the damage. What nutrients and “natural capital” were swept away in the process, we’ll never know.

Myths some people held about nature back then probably seem very strange to us today. One was the belief that when a bear stole a pig it did so while standing upright and cradling it in its arms like a baby.

Seemingly all snakes in those days were “copperheads” or “rattlesnakes.” According to one claim, 354 rattlers were killed by loggers in a single summer. It’s a mistake, of course, to assume that anyone living “close to nature” – as we assume all people in pre-park days did – were “nature experts.” Like us today, they were fallible and held prejudices, which is to say they were human. Today we know that over twenty snake species live in the park and that harmless species are still often misidentified as venomous by many people.

People also possessed a great deal more expertise and knowledge in many areas than we do today. The Walker Sisters of Little Greenbriar lived off the land all their lives, tending three kinds of cherry trees, twenty-one kinds of apple trees, and over one hundred flower species. No doubt Nancy (Caylor) Walker, born a half-century earlier, could have bragged similarly about her skills in growing what today we would call heirloom species. Her garden resided somewhere between where the Tremont office and Council House sit today. What memories the earth holds in that place of flowers past we can only imagine.

Growing boxwoods was a Walker family tradition, as it was for many people living in the Smokies, and Nancy probably took great pride and pleasure in planting these around her home. Though once likely very common in this area, no evidence remains of this plant on campus today. However, you will see the plant along Middle Prong Trail, roughly two miles from the trailhead.

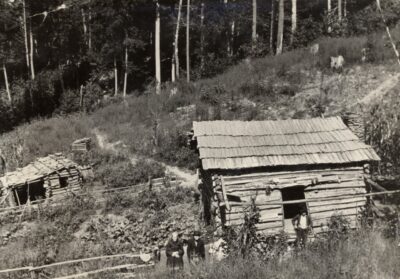

Yucca is another plant that was once likely very common around Tremont during Will and Nancy Walker’s day. The only specimens of yucca known to exist in Tremont is located near where Mary Ann Moore’s cabin resided, close to the West Prong trailhead. (Mary Ann and her son are pictured in the header above.) One presumes that many more once existed in this location, at Will and Nancy’s cabin, and at Moll Stinnett’s.

The Girl Scouts reported that pink lady’s slippers bloomed yearly near the Hunters unit. However, sometime around the end of the Camp Margaret Townsend session in 1959, somebody dug them up. “Everybody was pretty sad over that,” said Alice Heap, a former counselor at the camp. There was also a flame azalea bush by the river below the craft house. It’s long gone, too.

Mountain Camellia (Stewartia), an uncommon tree, once grew near the dining hall. “Those have gone with the modern construction here, which is too bad because they were beautiful trees,” said Heap. Whatever might remain of their roots lies buried beneath the Tremont staff apartments.

For many years, I searched the Spicewoods in vain for the plant for which that place is named. The Stinnetts and Cooks once lived there, of course, clearing trees and farming the hillsides and valley bottom. Spicebush, I assumed, was forever gone from the sheltered hollow bearing its name.

Then about ten years ago, while exploring the Spicewoods, I found spicebush growing. Possibly it was there all along, hiding away. Or perhaps birds and wind had finally carried seeds there helping to get it reestablished. Regardless, spicebush’s return stands as a testament to the renewing power of nature to restore things to their rightful place.