Community Science in 2023

Community science, formerly known as citizen science, embodies the spirit of collaborative exploration and discovery. It’s about everyday people coming together to contribute to scientific research in meaningful ways. Whether you’re a student, a teacher, or simply someone passionate about the natural world, community science invites you to come together observe, learn, and make a difference.

At Tremont, community science is not just a program; it’s a cornerstone of our mission to foster connections between people and nature. Through hands-on participation in real research projects, our volunteers not only expand their scientific knowledge but also deepen their bond with the natural world around them. Each observation, each data point, is a testament to their dedication and curiosity.

In 2023, we continued our journey of exploration, with volunteers contributing observations on a wide range of topics, from trees and wildflowers to salamanders and birds, but what makes this year’s report particularly special is the collaboration it represents. While much of the data comes from our local volunteers, we are thrilled to include contributions from researchers outside of Tremont. This collaboration not only enriches our understanding of the Great Smoky Mountains ecosystem but also underscores the power of collective effort in scientific inquiry.

Vernal Pond-Breeding Amphibians

In early 2023, Travis Roney, a citizen scientist at Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in Maryland, reached out to Tremont with the spirit of collaboration across our two organizations, in particular to share ideas and practices for our amphibian monitoring programs. Both Tremont and Jug Bay work with volunteer scientists to help monitor and protect spotted salamanders and other amphibians, and there is no replacement for in person experiential explorations, so we invited them down to Tennessee!

Jug Bay and Tremont teams after a day of vernal pond monitoring and spotted salamander spotting. Photo by Jeanette Kazmierczak.

What started as a straightforward exchange of ideas and an obvious shared love of amphibians ended in…well, didn’t end at all! Tremont staff and volunteers left the weekend feeling deeply inspired and connected to our mission and monitoring here in the Smokies, and also feeling that we are not alone but rather a piece in a larger community of dedicated, passionate volunteers who spend their time and love protecting our amphibious friends. We continue to be inspired by the work of Jug Bay and its volunteer science team, which recently held its own Citizen Science Summit to share the work and results of their volunteer science programs, many of which are directly analogous to those we do at Tremont (including a MAPS banding station, vernal ponds, and monarch butterfly programs) as well as wetland specific studies.

Diving into the Data

One concern we had as the Jug Bay folks planned their trip to the Smokies was the lack of water in the vernal pools even into late January. No water means no appropriate habitat for our pond-breeding amphibians such as spotted salamanders and wood frogs, which require aquatic environments for eggs to develop into larvae. Each year, in addition to quantifying the egg masses of each species throughout the breeding season (late January through early March), we also take environmental data including water temperature, pH, and depth at defined locations throughout the pools.

Tremont Volunteer Walt Peterson shares tips and protocols for measuring the depth of Gum Swamp during our vernal pond amphibian breeding season. In some years, the area in which we are standing in the above photo is underwater.

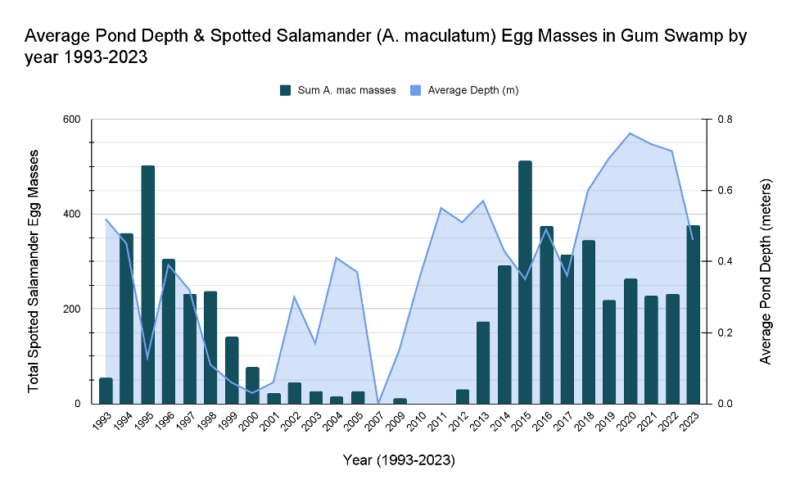

So how does water depth impact our target species? The answer can help us understand why long-term monitoring is so important. 2023 marks our 30th year of data collection using the same protocols to study trends in amphibian breeding populations. These three decades help show us longer patterns in populations and the possible relationship between hydroperiod and breeding population.

Total spotted salamander egg masses and water depth (m) by year. Each egg mass represents one breeding female.

What seemed like an exceptionally dry year to those of us who have only been monitoring since 2019 in fact was average or above average when viewed over the entire study period. What’s more, the impact changes in hydroperiod have on spotted salamanders is not immediate but experiences a lag, possibly due to their life history. Spotted Salamander metamorphs that leave temporary pools in the Smokies may take 3-4 years to reach sexual maturity and return to these same ponds as adults. This means that winters in which the ponds retain water long enough for all salamanders to emerge from the ponds (higher success rate) may not be reflected in the following year’s numbers but rather could be reflected in the egg mass count 3-4 years later. This could explain why the population struggled to recover between 2000 and 2013 after being hit with ill-timed droughts and short hydroperiods.

A spotted salamander is found and gently held by a Jug Bay volunteer. To protect their skin from chemicals that may be present on human skin, we should always wear gloves or handle salamanders in plastic bags to avoid direct contact.

Without long-term data, these trends would be nearly invisible to us, in particular since we as humans shift in and out of staff and volunteer positions, move around, and shift our baselines. Continuously using the same protocols means that our data outlast our own observations and tenure in any place, and when we contribute to larger projects through citizen and community science we add to the legacy of understanding the world around us.

Huge warm thanks to the entire Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary team (Travis Roney, Allison Burnett, Michelle Campbell, Jeanette Kazmierczak, Jessica Roney, Eva Blockstein, Liana Vitali, Katy Clark, Michael Wagman, and Christina Olson), as well as Tremont’s dedicated team: Walt Peterson, Laura Dixson, Mark Weingartz, Mac Post, Tracy Tolley Hunter, Madeline Walker, Lark Heston, Carrie Schmitt, and David Bryant.

The Snakes of Second Campus

At Tremont, we aspire to create a world where individuals are deeply connected with nature, and we’re building a second campus to make this a reality. In 2019, we purchased 194 acres adjacent to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Townsend. Since then, we have devoted ourselves to exploring, understanding, and caring for this land. Learn more about our second campus.

Contributed by Joe Gordon, Johnson University professor, Tremont volunteer, and Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program graduate

Year two of snake population surveys on the second campus has been quite successful. Check out our findings from year one!

In 2023, there were fifteen surveys of the plywood and tin cover objects—at least one survey every month of the year except for August—and we encountered snakes every visit with the exception of the final survey in December!

This year, we only saw four different species, but we did turn up one new one—I regularly encountered one or two Eastern Wormsnakes (Carphophis amoenus amoenus) underneath a discarded welcome mat in a closed canopy pine-oak forest. That brings the total species count for the property to seven—the Wormsnake is added to a list which also includes:

- Cornsnake (Pantherophis guttatus)

- Midland Ratsnake (Pantherophis spiloides)

- Northern Black Racer (Coluber constrictor constrictor)

- Northern Brownsnake (Storeria dekayi)

- Northern Ringneck Snake (Diadophis punctatus edwardsii)

- Eastern Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix)

There were 34 distinct snake encounters during the surveys this year, including the Wormsnakes and multiple individual Racers, Ratsnakes, and Cornsnakes.

A “Snakie” with one of my Cornsnake friends in November 2023.

Eastern Wormsnake (Carphophis amoenus amoenus); by Joseph K. Gordon

During a survey in April, we were surprised to interrupt two Racers making more Racers underneath one of the tins!

In July, I witnessed a remarkable natural history event: one of the adult female Cornsnakes I encountered exhibited cloacal autohemorrhaging; in addition to normal musking, she excreted and smeared blood from the musk glands at the base of her cloaca (the multipurpose vent that snakes have for reproduction and waste elimination) on me. This probable anti-predator behavior has only been reported for a handful of snake species, and never for Cornsnakes. I have written a natural history note on the observation, hopefully to be published in Herpetological Review.

Thanks to my students and colleagues in the Johnson University hiking club and my Creaturely Theology course for help with three of the surveys, to my niece Julia and brother-in-law Ben for help with another survey, and to Elizabeth Davis and John DiDiego for spontaneous snake spotting. Elizabeth and I are setting up more cover objects this winter in hopes of finding new species in the coming year!

Bird Banding

Once every ten days during the summer months a group of dedicated volunteers gathers before sunrise to set up 13 mist nets around Tremont’s National Park campus. We follow a protocol called Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) that surveys birds during the breeding season through bird banding. In 2023, the mist nets caught birds 106 times! 18 total species of birds were caught in the nets this year, including warblers, wrens, chickadees, thrush, and many others. 2023 was a big year for Wrens! We banded more Carolina Wrens (11 total) in 2023 than any year since 2013.

Every net is designated a number that is recorded each time a bird is caught. Each net is set up in a particular habitat, for example in a field, near the river, or in a forested area. Who we catch and where we catch them teaches us a lot about the species in the area and the habitats they prefer. Just as important is who we do not capture, in particular when a species used to be present in the valley but is no longer seen or heard with much frequency.

A male indigo bunting perches atop branches as a female sits below.

In Walker Valley, one such species is the Indigo Bunting, Passerina cyanea. This small, beautiful bird in the cardinal family eats seeds and insects and is found in edge habitats. In the springtime, the male Indigo Buntings sit on the very tops of trees or phone lines to sing. Their call is a series of paired notes which some say resemble the sounds “fire fire, here here, quick quick, put it out put it out!” Because of this behavior, we tend to see these birds in big fields such as Cades Cove, Seven Islands State birding park or, historically, in the little field near the Tremont office and pump house.

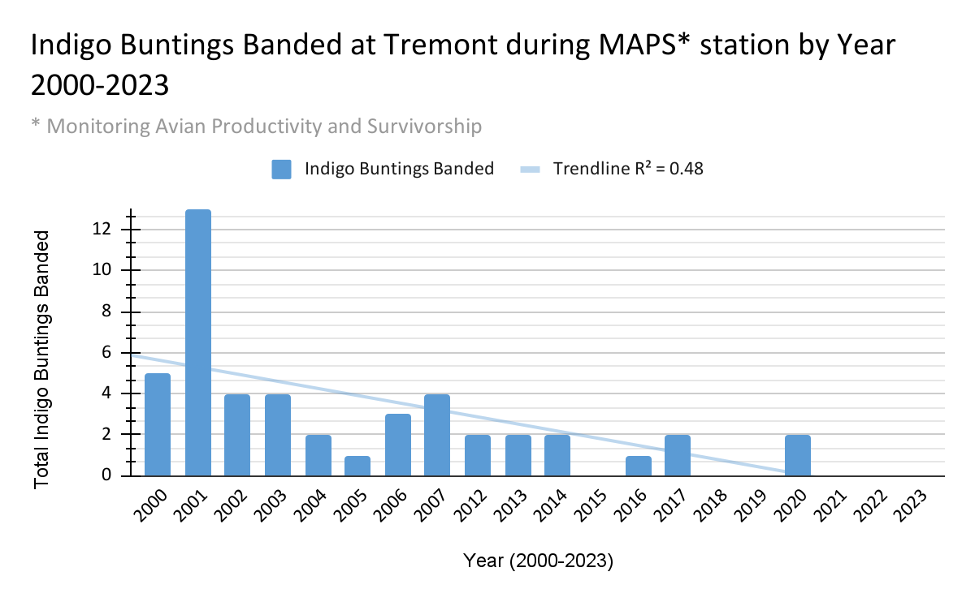

In 2023 we did not catch a single Indigo Bunting, which followed patterns from the previous two years (Figure 1). So why the decline in this species? There might be many answers to this question. While it is true that there has been a massive and devastating decline in birds in the United States over the past few decades, here at Tremont even when we were catching buntings the total number caught was never very high (excluding the outlier of 2001 in which 13 individuals were reported).

Figure 1. Indigo Buntings caught in mist nets during MAPS seasons from 2000-2023 (missing data from 2008-2011).

It’s possible that the loss of our breeding buntings has more to do with the changes in habitat that no longer suited their behaviors and needs. In the past, we frequently caught these birds in the nets associated with open spaces or fields. Over time, a pause in intentional management of these areas as fields has resulted in some environments, including the little field across from Tremont’s office, becoming more overgrown with young trees taking advantage of the light to grow taller. While this is just one theory, we will return to clearing these spaces, which are important not just for birds but also many flowering species of plants including milkweed, the host plant for the monarch butterfly caterpillar.

While often human impacts are described as damaging to nature, the truth is humans are deeply a part of nature, and we can both enhance or harm our ecosystems. Maintaining these natural “grasslands” or field areas with native grasses and flowering plants increases the biodiversity of the system and provides healthier habitats for many species, including our summer resident birds.

For their flexibility with weather, early mornings, careful handling of birds, and engagement with the public and each other, a heartfelt thanks to Stephanie Mueller and Clare Dattilo, Paul Super, the Metcalf family, the Geagley family, Holly Hoyle, Gar Secrist, Will Kuhn + DLIA interns, Kat Livar, Sarah Wilcer and her Cades Cove team, Morrigan Timothy, Wren Logan, Daniel Webb, Faith Reed, and Madeline Walker

Butterfly Education Program

A Great Spangled Fritillary rests for a moment on a participant’s nose before flying back into the fields. Photo by Rich Bryant.

Each fall the annual migration of monarch butterflies (Danaus Plexippus) gives Tremont’s volunteer Butterfly Education Team the opportunity to bring in hundreds of members of the public to Cades Cove to learn about the huge diversity of butterflies in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. In 2023, our core education team helped over 350 participants explore these ecosystems and use field guides to identify 579 non-monarch butterflies of 34 different species that call the Smokies home.

While we may love our migratory monarchs (and in 2023, we caught and tagged 724 of these special butterflies!), learning to notice and identify other species is a priority for the Education team, as we believe that noticing the diversity of species is an important step to caring for these ecosystems.

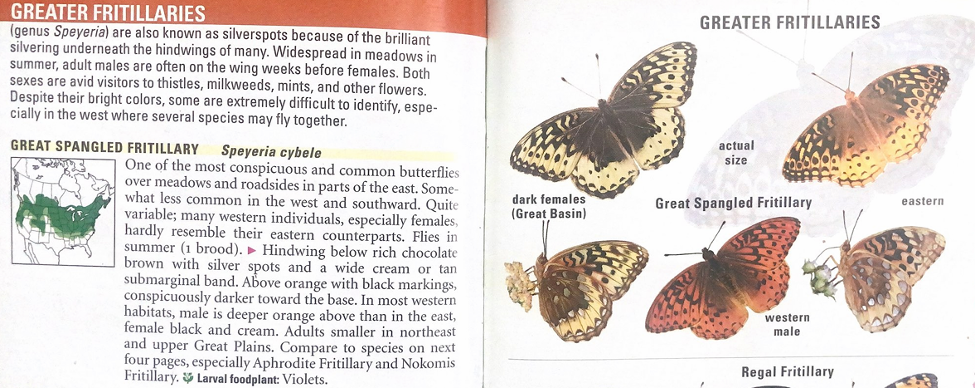

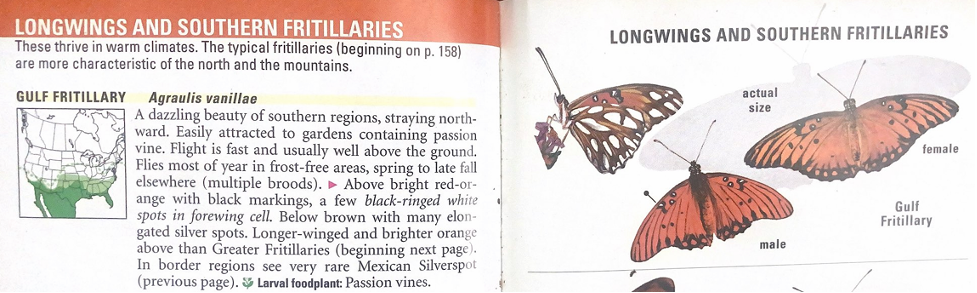

Of the 34 species of butterflies identified, three species were in a group of butterflies known as fritillaries. Like all species of life, butterflies are grouped together through taxonomy, or the classification and naming of species with shared evolutionary history and, sometimes, physical traits. The fritillaries are in the family Nymphalidae, commonly known as the Brush-footed or Brushfoot butterflies, which includes monarchs. Fritillaries are in what is known as a sub-family called Heliconiinae, which also includes longwing butterflies.

Great Spangled Fritillary feeding on its host plant. Image source.

Many people are aware that monarch butterflies require milkweed as caterpillars, but did you know that many other species also have specific food sources as caterpillars? The Great Spangled Fritillary pictured feeding on its host plant: violets.

While some people think monarch butterflies are the only star of the show, our Butterfly Education Program welcomes participants into the astounding biodiversity of butterfly life found in the Great Smoky Mountains. In turn, participants help us gather important data about the species presence, distribution, and abundance over the course of the fall season. This data is then used to compare previous and future participants’ observations to track changes to the health of these integral ecological community members.

For their continuous learning and thoughtful, patient education of our community on butterfly habitats and natural history- a massive thank you to Wanda DeWaard, Terry Uselton, Mac Post, Lark Heston, Gar Secrist, Walt Peterson, Mark Weingartz, Carrie Schmitt, Laura Mallette, Juli Rigell, Hall family, Metcalf family, Geagley family, Davis and Powell family, and Neilson family. Big thanks as well to every community member who joined us in the field this year to learn more about our habitats and the species that we live with. We hope you spread the word and notice more plants and butterflies back in your own homes and wild spaces!

Try Your Hand at Butterfly Identification

When participants find a butterfly, our educators will ask them questions to help them use guides to narrow down the identification of the insects. Take a look at the following photos. What colors stand out to you? What similarities do you notice between these two butterflies? Differences?

Through observations and a reference like the one below, you may be able to distinguish between the Gulf Fritillary and the Great Spangled Fritillary.

Click arrows to turn the page. Excerpts from Kaufman Field Guide to Butterflies of North America, a favorite field guide we use for our Butterfly Education Programs.

Second Campus Pollinators

One of the benefits of our second campus is that we get to practice land management and stewardship in new ways. For the first time, we are able to independently make decisions about how we engage with the land, which includes our relationships with third-party researchers.

Laura Russo is an Ecology & Evolutionary Biology professor at the University of Tennessee. When she reached out to partner with us for original research on native plant preferences of native pollinators, we jumped at the opportunity to collaborate on research that could inform the species we choose to plant to enhance the biodiversity of the land.

Phenology

Daniel Metcalf has been volunteering for Tremont science programs since he was a kid. Daniel is now an undergraduate student at the University of Tennessee studying Nuclear Engineering and Physics with a minor in Engineering for Sustainability. In his free time, he still comes out to Tremont to observe his trees in his family’s phenology plot, help set up bird banding nets, carefully remove birds from nets, and interpret the banding process to the public, and he also helps to guide members of the public in butterfly identification and monarch tagging each fall.

The trees rustled in the breeze as I gazed up at them. “Hey, come look at this,” I called to my family, “Tree #7 has fruit!”

I was nine when my Mom learned about the community science program at Tremont in 2013, and we quickly joined the phenology program. An opportunity to visit a plot of trees across the changing seasons and contribute to ongoing scientific research? How could we pass that up? At our first training, we learned about the different factors to record: leaf size, leaf color, canopy cover, flowers, and so on. These data go into a national database to help create a better understanding of the changing of the seasons.

We were assigned the Nature Trail, a plot in the heart of Tremont’s campus with a couple dozen numbered trees. For the past decade, now, we have visited it roughly every other week through the spring and fall, gathering data on our trees and developing a close connection to the area. From the beginning, I have monitored the first few trees up to #11 (though I now check several more), and I have grown very fond of them. All young trees growing beneath the upper canopy, they are a ragtag bunch. They reach for light wherever they can find it, and several have not survived. None of them had ever had any fruit. Until this fall, that is.

Tree #7, one of the biggest in the understory, is a musclewood tree (also known as hornbeam or ironwood). Musclewood fruits look almost like bunches of leaves, but I’ve become quite familiar with identifying them in our older trees. As I gazed up at tree #7 this fall, I was surprised to see what looked like fruit. I checked with my binoculars, and was certain: tree #7 had matured! My mom excitedly texted Erin Canter, who coordinates the community scientists: “We feel like our little baby is all grown up now.”

For their careful concentration on their designated trees, thank you to Mac Post, Kimber Bradbury, Cheryl Brodbeck, Gail Broxson, Karen, Daniel, and Hannah Metcalf, Sarah Geagley, Mark Weingartz, Tammy Pilkington, Travis Whitehead, Terry Uselton, and Allison and Rodney Pearson.

Hannah Metcalf looks on as Daniel attempts to get a photo of tree #7 to document this little tree’s first fruit! Photo by Karen Metcalf

American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) fruits resemble dried seeds when ripe. Volunteers develop a keen eye for the flowers, leaves, and fruits of each different species they monitor.

How to Identify Fronts Using Weather Data

At Tremont, we take data daily from our weather station in order to help predict the day’s weather and prepare for our outdoor adventures. We’ve been doing this with school groups going back three decades! Geologist and Tremont volunteer Greg Mudd helps explain one phenomena you may often hear about when interpreting weather data: cold and warm fronts.

Weather data such as temperature, humidity, precipitation, air pressure, wind speed, and wind direction are key observations of the atmosphere that help forecasters with the National Weather Service (NWS) and other entities predict the weather. So how do forecasters use the weather data to predict the weather? They do so by tracking fronts.

Have you ever looked at a weather map and noticed blue curved lines with blue triangles? Or how about red curved lines with red half circles? Or even purple lines with both purple triangles and purple half circles? These lines mark what are known as fronts moving across an area.

A front can be defined as the transition zone between two air masses of different temperature and humidity. Fronts can extend over a very short distance (30 miles), or over a very long distance (several hundred miles). The frontal zone represents the boundary between the two different air masses. If the cold air mass is moving into an area of warmer air, the front is called a cold front. If the warm air mass is moving into an area of cooler air, the front is then called a warm front.

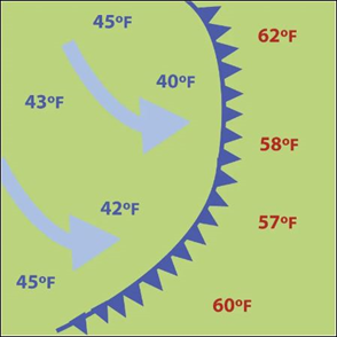

According to the NWS, a cold front can be defined as: “A front in which a cold air mass is replacing a warm air mass at the surface”. The symbol on a weather map that is used to identify a cold front is a blue line with triangles that point in the direction in which the cold front is moving. The line represents the leading edge of the cooler air mass, as depicted on the diagram on the left below. The numbers on either side of the front represent the surface temperatures in degrees Fahrenheit. Notice the temperature change from one side of a cold front to the other. The stations east of the front reported temperatures ranging from 57 to 62 degrees Fahrenheit while a short distance behind the front, the temperature decreased to a range from 40 to 45 degrees Fahrenheit. An abrupt temperature change over a short distance, along with the presence of clouds, is a good indicator that a front is located somewhere in between.

According to the NWS, a cold front can be defined as: “A front in which a cold air mass is replacing a warm air mass at the surface”. The symbol on a weather map that is used to identify a cold front is a blue line with triangles that point in the direction in which the cold front is moving. The line represents the leading edge of the cooler air mass, as depicted on the diagram on the left below. The numbers on either side of the front represent the surface temperatures in degrees Fahrenheit. Notice the temperature change from one side of a cold front to the other. The stations east of the front reported temperatures ranging from 57 to 62 degrees Fahrenheit while a short distance behind the front, the temperature decreased to a range from 40 to 45 degrees Fahrenheit. An abrupt temperature change over a short distance, along with the presence of clouds, is a good indicator that a front is located somewhere in between.

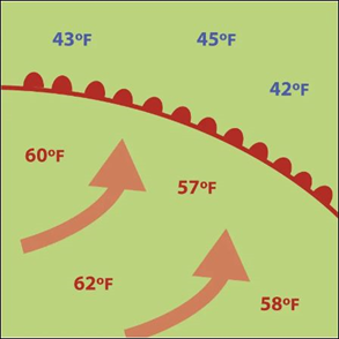

Conversely, a warm front can be defined as a front in which a relatively warm air mass is replacing a colder air mass at the surface. The symbol that is used to identify a warm front on a weather map is a red line with half circles that point in the direction in which the warm front is moving. A warm front is depicted below on the diagram on the right. Notice that the surface temperatures behind the front are higher than those in advance of the front. As with cold fronts, clouds form along warm fronts as well.

Conversely, a warm front can be defined as a front in which a relatively warm air mass is replacing a colder air mass at the surface. The symbol that is used to identify a warm front on a weather map is a red line with half circles that point in the direction in which the warm front is moving. A warm front is depicted below on the diagram on the right. Notice that the surface temperatures behind the front are higher than those in advance of the front. As with cold fronts, clouds form along warm fronts as well.

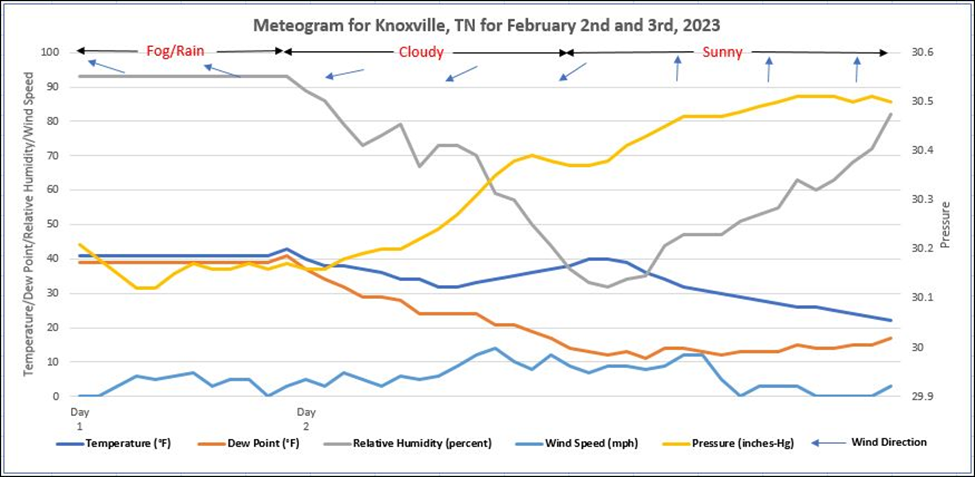

Although weather maps are good for giving an overall perspective of the “big picture,” they can be difficult to help determine what will happen in your area. Therefore, meteorologists can detect fronts not only on weather maps, but also by looking at a chart known as a meteogram. A meteogram is a time cross-section of data for a specific reporting station. The data plotted include weather data parameters, such as temperatures, dewpoint, relative humidity, wind direction and speed, as well as the present weather conditions.

By looking at a meteogram, meteorologists can see how weather conditions change over a given period of time. The meteogram below was created from weather data reported by the NWS for Knoxville, Tennessee during an approximately 36-hour period between the latter part of February 2nd, 2023, and all of the following day. We saw in the discussion above regarding fronts that when a cold front passes through an area the pressure and temperature both drop, the winds shift from a primarily southerly direction (coming out of the south) to a more westerly or northerly direction, and precipitation develops.

In the meteogram, time is shown along the horizontal axis at the bottom of the chart. The precipitation conditions are plotted along the top of the chart along with the wind direction. The barbs on the wind direction arrows point in the direction the wind is coming from. The wind speed is represented by the light blue line shown in the power portion of the chart. The lines representing the temperature, dewpoint, relative humidity, and pressure are shown in the central portion of the chart. Only the latter portion of Day 1 is shown on the chart. The weather conditions at that time were rain and fog. The temperature and dewpoint at that time of Day 1 were very close and the humidity was relatively high. The barometric pressure was also relatively high. The wind was relatively low and blowing generally from west to east on Day 1.

As Day 1 turned to Day 2, the rain stopped and the temperature and dewpoint began to drop and to diverge, suggesting that cooler, drier air was moving into the area. The wind speed and direction during the initial stages of Day 2 suggest that the front had not quite moved through the area. About mid-day of Day 2, the wind changed direction to the north and the speed decreased significantly. The temperature continued to drop as the front continued to migrate southeastward. During the latter part of Day 2, the humidity increased again, and the dew point began to get closer to the temperature.

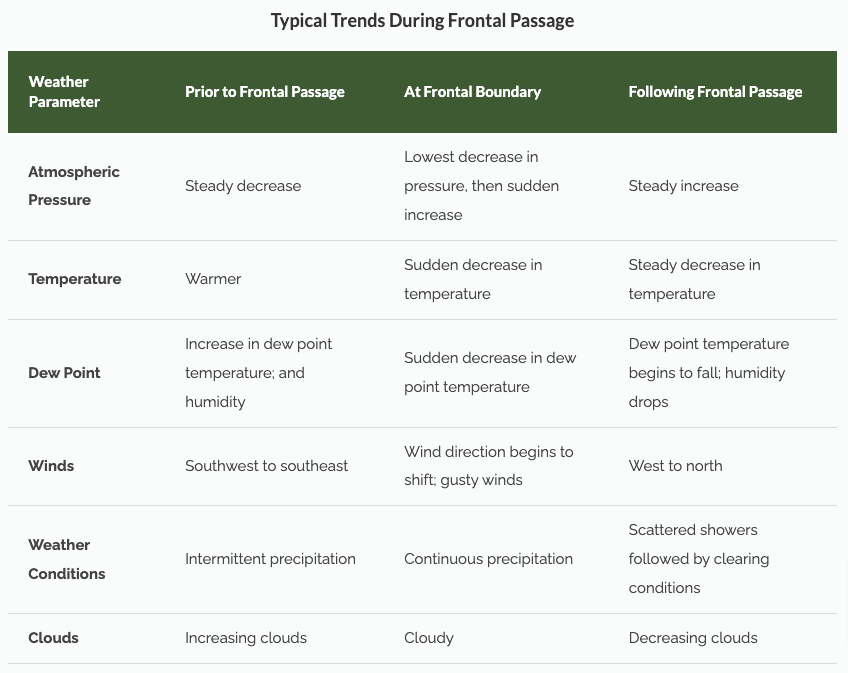

So, to summarize, in order to recognize when a cold front is approaching your area, look for the trends in the weather parameters listed in the table below.

Get Involved

All of these programs run because of engaged and curious community members who volunteer their time and knowledge to help us all learn more about our world and our place within it. If you are interested in volunteering to support Tremont’s community science projects, please fill out the volunteer application. Note that most community science projects require a training session and long-term commitments, though many only require a few hours each month, seasonally. Not all projects are suitable for young children.

Call for science communicators! We are currently looking for data-savvy volunteers who like to analyze numbers and communicate the results for public understanding. If this is you, email us at [email protected].